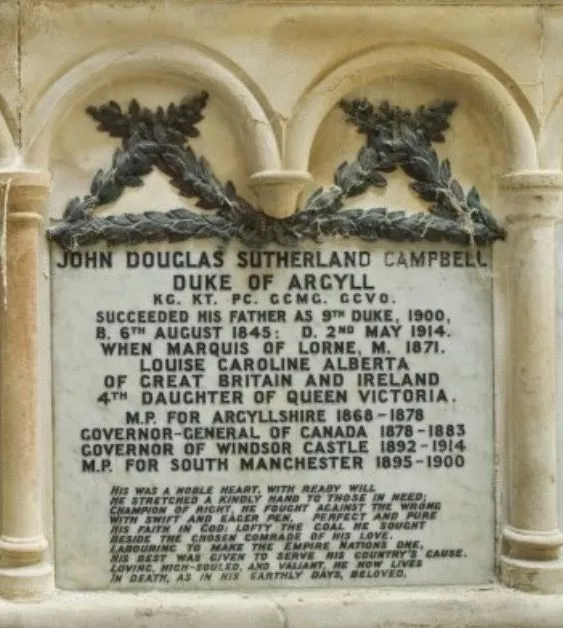

John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll (S), 2nd Duke of Argyll (UK), KG, KT, GCMG, GCVO, VD, PC (1845 - 1914)

John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, 9th Duke of Argyll (S), 2nd Duke of Argyll (UK), Governor General of Canada, and author; eldest son of George John Douglas Campbell, Marquess of Lorne, later 8th Duke of Argyll (S), 1st Duke of Argyll (UK) and his first wife Lady Elizabeth Georgiana Sutherland-Leveson-Gower; m. 21 March 1871, in Windsor, England, HRH Louise Caroline Alberta Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Princess of the United Kingdom, 4th dau. of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. He was styled, Earl of Campbell from 6 April 1845 till 25 April 1847, and best known as the Marquess of Lorne from 25 Apr 1847 till 24 Apr 1900.

9th Duke of Argyll (S),

2nd Duke of Argyll (UK),

KG, KT, GCMG, GCVO, VD, P

John Douglas Sutherland Campbell – he was known in the family as Ian – assumed the courtesy title of Marquess of Lorne in 1847 when his father succeeded to the dukedom of Argyll. His home was Inveraray Castle, where his father, who never smoked or drank and had a horror of excess, presided with some authority. A Peelite, from 1853 to 1866 the duke held a succession of offices under Lord Aberdeen and Lord Palmerston. The duchess, a daughter of the Duchess of Sutherland, absorbed her mother’s liberalism, supporting such women as Elizabeth Fry and Florence Nightingale. Ian went to Eton College, Windsor, Berkshire, England. then briefly to the University of St Andrews in Scotland, and finally, after a year’s tutoring in classics, to Trinity College, Cambridge University, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England. But classics were not his bent. What he wanted was science, history, modern languages.

The American Civil War and the Jamaican disturbances of 1865 suggested that there was more to the world than Greek and Latin verbs, and in 1866 Lorne arranged to visit Jamaica. His first book, A trip to the tropics and home through America, came out in London the following year. He spent a season (1866–67) at the University of Berlin, improving his German, and went to Italy in 1867. His father concluded that, given Lorne’s facility for modern languages and his literary gifts, his education was better improved by travel than by Cambridge.

Offered the House of Commons seat for Argyllshire, which was virtually in the family’s pocket, Lorne was elected in 1868 and sat until 1878. His contribution to the debates was minor. His main work was as private secretary in 1868–71 to his father, whom Prime Minister William Ewart Gladstone had appointed secretary of state for India.

Lorne had a flirtation with Gladstone’s daughter Mary, but it waned and in 1870 when higher authority intervened. In 1870 Princess Louise, the most beautiful of Queen Victoria’s daughters, was 22. Although not since 1515 had an English princess married outside a European, continental dynasty, she and the queen now devised a private list of five British candidates. In September 1870 each was invited to spend a few days at Balmoral Castle. The last young man on the list, and probably the most important in the eyes of the queen and possibly Louise, was the Marquess of Lorne.

Lorne and Louise were married in March 1871 at St George’s Chapel in Windsor Castle. They soon moved into Kensington Palace, where the queen had been brought up. A few years passed, but no children were in sight. Rumours began that have continued to the present day. Was there sexual ambiguity in Lorne? There were those who saw evidence of it in his literary and artistic tastes and talent, and in the fact that his uncle Lord Ronald Charles Sutherland-Gower was almost certainly homosexual. Lorne’s attitudes, however, are by no means clear. Historian Sandra Gwyn suggests strongly that he had homosexual inclinations. If so, they were not altogether obvious. The absence of children proves nothing. Louise may never have been able to produce them. A Campbell rumour was that she had never had menstruation, but this tale was not substantiated. She was outgoing and vivacious, and could be as imperious as her mother. Lorne was quiet, reflective, guileless, an observer rather than a doer. He may have had mild sexual drives, or found Louise’s enthusiastic sexuality disconcerting. A lukewarm sexual temperature in Lorne is probably the most convincing explanation of their relationship, for it lasted a long time despite vicissitudes and Louise was devastated by his death.

In 1878 Lorne was appointed Governor General of Canada by British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli, to succeed Lord Dufferin [Blackwood*].

The queen’s approval had been secured before the offer was made. She hated to be parted from her daughter, but Prince Albert had always favoured their children being useful in the colonies. Lorne and Louise arrived officially in Halifax on 25 November. He was sworn in at Province House at 33 years of age, Canada’s youngest governor general. Though he had none of Dufferin’s endearing joviality, he was by no means a bad choice. Quick, perceptive, and adaptable, he gradually became Canadianized and rather enjoyed the informal style of the New World, though sometimes disliking its politics.

Lorne’s first political encounter was with the appointment of Canada’s first high commissioner to Britain, in 1879. The British government was dubious; Lorne’s advice was that it accept the idea. More and more would Canada want to make treaty arrangements with other countries, and having its own representative in London might put this idea off. He asked his father to help the appointee, Sir Alexander Tilloch Galt*, socially, for there were problems. Lady Galt was the sister of Galt’s first wife, and her marriage would have been prohibited in England. Sensitive to slights, Galt claimed he would have to resign if his wife was not received at court. Owing probably to interventions from Lorne, Louise, and the Prince of Wales, the queen did receive her, deceased wife’s sister though she was. To help settle Galt further, Lorne gave him good advice in 1880: concentrate at first on the formalities of the office and only gradually raise the prickly political and commercial issues. Gladstone’s ministers, he wrote with some inside knowledge, were in no state to have their “digestions overloaded.”

A more serious question for Lorne was the dismissal of the lieutenant governor of Quebec, Luc Letellier* de Saint-Just. Letellier had discharged a provincial Conservative government and installed a Liberal one. The action was vindicated in the provincial election of May 1878, but the Liberals emerged with a majority of only one. Outraged, Quebec Conservatives vowed to have Letellier’s head if they won Quebec in the federal election in September, which they did. Prime Minister Sir John A. Macdonald* would have preferred leaving Letellier alone, for his term would end in 1881, but Macdonald’s French Canadian followers would have none of that exercise. So he had to face the disagreeable task of persuading the new governor general to sign the order in council dismissing Letellier. Lorne was not persuaded. His view, in April 1879, was that Henri-Gustave Joly*, Quebec’s Liberal premier, had taken on the political responsibility for Letellier’s actions. Lorne did not like the use of federal power such as Macdonald was contemplating. Lacking a precedent, he justifiably referred the matter to the Colonial Office in London. In the end Lorne was instructed to act in conformity with the advice of his ministers. Letellier was dismissed on 25 July.

In the long run more important things, in the realm of national culture, measured Lorne’s capacity. He virtually created the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts. Dufferin had advocated it and Lorne, supported by Lucius Richard O’Brien* and others, won over Quebec and Ontario artists to the idea. In March 1880 the Canadian Academy of Arts – Royal would be added in August – was launched in Ottawa with as much fanfare as Lorne could persuade the prime minister and the government to muster. The paintings that came as diploma works would be owned by the government, and in fact became the nucleus of the National Gallery of Canada [see John William Hurrell Watts]. The government did not take this responsibility seriously once Lorne had returned to England. From 1887 to 1911 Canada’s National Gallery shared premises with the fisheries exhibition.

In 1882 came the formal creation of the Royal Society of Canada. The previous year Lorne had proposed a national academic association that would comprehend science and letters in both French and English [see Sir John William Dawson*]. The French-speaking community took up the idea with alacrity; in English-speaking Canada there was scepticism. Lorne’s tour of the prairies in 1881 strengthened his resolve; he learned that the Smithsonian Institution had been there gathering Indian artefacts and had carted them off to Washington, D.C. The inaugural meeting of the society was held in the Senate on 25 May 1882. Lorne believed the Royal Canadian Academy and the Royal Society were part of a Canadian renaissance. “Just as in some war periods,” he would philosophize to John George Bourinot*, “so in the time when great enterprises like the [Canadian Pacific Railway] were undertaken, adornment and elevation of thought is coincident with sterner effort.”

Lorne’s impressions of the west were stamped into his being in 1881, just as the CPR was being built. His expedition across the prairies, which left the end of steel at Portage la Prairie, Man., on 8 August, included a large party from Rideau Hall (Louise was then in England), a North-West Mounted Police escort, and substantial representation from the newspapers, both Canadian and British – some 77 men and 96 horses. Lorne was stunned by the beauty of the west, especially at Fort Calgary (Calgary). He made speeches about it afterward in Winnipeg and elsewhere, and the press published his sketches. He was tremendously exhilarated by the trip, which ended in October. Lorne’s concerns comprehended Métis claims, Indian treaties, and the NWMP. He was a good listener and in late October he presented Macdonald with a long memorandum on what he had heard. He noted that the sympathies toward the Métis and Indians of Lieutenant Governor David Laird had been little appreciated in Ottawa and in the east generally, and he urged that the NWMP be strengthened. He pointed out how Spartan their quarters were compared with those of the American army. Lorne was realistic about what was possible, noting, via his aide-de-camp, that agriculture in the Bow River valley was still an uncertain question. The opinion among the governor general and his entourage was that ranching was probably the most workable possibility, provided that “capitalists like [Matthew Henry Cochrane*] could be prevented from getting everything into their own hands.”

The impact on Lorne of this western trip would show ever after. He may have been the only British governor general to put the word home in quotation marks, gradually finding he preferred Canada to Britain. He joined Louise in England in November; the winter of 1881–82 he found dark and unwholesome after the Canadian one, with its “bright light and the dry and beautiful snow with its sapphire coloured shadows.” There spoke the outdoorsman and the landscape artist!

In September 1882 Lorne brought Louise to British Columbia via San Francisco. Dufferin had been in British Columbia six years before, patching up relations between the young province and Ottawa. Lorne was well capable of helping Macdonald’s CPR policies sit better with the British Columbians. He really began the process of persuading Victoria’s politicians of Ottawa’s sincerity. The welcome given Lorne and Louise was soon reciprocated. They both loved the climate and the scenery. For Lorne an additional attraction was the adventure that the interior offered – he was there when William Cornelius Van Horne, general manager of the CPR, announced the discovery of the Rogers Pass through the Selkirks; for Louise it was the informality of her stay at Cary Castle, the residence of the lieutenant governor. Having sailed from Victoria in December, the Lorries travelled back through the southern United States. Lorne came straight to Ottawa but Louise, who wintered in Bermuda, did not return until April 1883; they were together for the close of the session of parliament in May.

Lorne now felt that his life and marriage required his resignation as governor general. Terms were normally six years; he had had five. He regretted this decision, for he loved the country, saying to Macdonald, “I should like to stay here all my days.” He left Canada in October. His years there were the happiest he had known, or perhaps would know. Many of his publications of the 1880s dwelt on Canada with enthusiasm; Canadian pictures, drawn with pen and pencil (London, [1884]; [new ed.], 1885), with Lorne’s own illustrations, achieved marked success as a travel book aimed at potential emigrants and it gave the Canadian west unprecedented exposure.

His success in Canada made it reasonable for him to anticipate future appointments, perhaps as lord lieutenant of Ireland or as viceroy of India. But the queen wanted her daughter close by, so Lorne busied himself with writing and with his Scottish estates. In 1900 he declined the governor generalship of Australia. He and Louise often went their own ways. The queen struggled for the sake of propriety to keep them under one roof, but admitted that Louise could not be forced to remain so. Even with Louise, Lorne was not received with the greatest cordiality at court; the Prince of Wales did not take to him. His connection with the royal family was at times a liability, as were his outspoken views on imperial federation and his estrangement from Gladstonian Liberalism. In 1885 and again in 1892 he tried without success to re-enter the commons; in 1895–1900 he sat as a Liberal Unionist for Manchester South.

Lord Lorne became the 9th Duke of Argyll on the death of his father on 24 April 1900. Lorne was 54. By this time Louise’s fetish with physical fitness had begun to show much to her advantage. Lorne, however, had become lethargic and as he grew older he was quite content with being sedentary. He continued to write. After Queen Victoria’s death in 1901 he wrote her biography, which was published in serial form and then as a book. It proved very popular, a sympathetic account with enough inside information to keep it lively.

In 1906 Lorne and Louise went to Egypt but he did not like it. “His heart,” his sister wrote, “is always in Canada.” This sentiment was symbolized by his last book, Yesterday and today in Canada (London, 1910), a warmed-over rendition of Canadian pictures. After 1910 his health declined, and in April 1914 he was stricken with pneumonia while visiting the Isle of Wight. He died there on 2 May and was buried in the ancient family burial-ground at Kilmun, Scotland.

Lorne was the first duke of Argyll in whom the arrogance traditional in the family was quite wanting. He never possessed the assertiveness and vigour of his father. He was a good example of a mid-Victorian dilettante, loving nature and literature; he was a discriminating observer of both. He was a good writer but not good enough – he lacked the blaze of real talent. Though he wrote much, he was not ruthless enough about what he published. But he loved Canada and was an excellent publicist for the new dominion just when it needed such promotion. His trip to the prairies and to British Columbia showed he had an excellent appreciation of the press, and his sketches and writings attracted public attention. He himself was caught and held by the beauty of the country. Louise found Canadian society vulgar and woefully unsophisticated. Her husband did something to remedy this state with the Royal Canadian Academy and the Royal Society of Canada. Lorne has been underrated as a governor general: few have wrought better than he.

Married: 21 Mar 1871 HRH Louise Caroline Alberta Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Princess of the United Kingdom, VA, CI, GCVO, GBE, DGStJ, (b. 18 Mar 1848; dsp. 3 Dec 1939), 4th dau. of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha. they had no issue; d. 2 May 1914 in Cowes, England. From 21 March 1871, her married name became Campbell.

She gained the title of HRH Princess Louise of the United Kingdom.

She was appointed Lady, Royal Order of Victoria and Albert (V.A.)

She was awarded the Imperial Order of the Crown of India (C.I.)

She was appointed Dame of Grace, Most Venerable Order of the Hospital of St. John of Jerusalem (D.G.St.J.)

She was appointed Dame Grand Cross, Order of the British Empire (G.B.E.)

She was appointed Dame Grand Cross, Royal Victorian Order (G.C.V.O.)

She was honorary Colonel-in-Chief of the Princess Louise's Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders.

After her marriage, Louise Caroline Alberta Saxe-Coburg and Gotha, Princess of the United Kingdom was styled as Duchess of Argyll on 24 April 1900.

Children: without issue

Born: 6 Aug. 1845, London, England

Died: s.p. 2 May 1914, Isle of Wight

Tenure: 24 April 1900 - 2 May 1914 (14 years, 9 days)

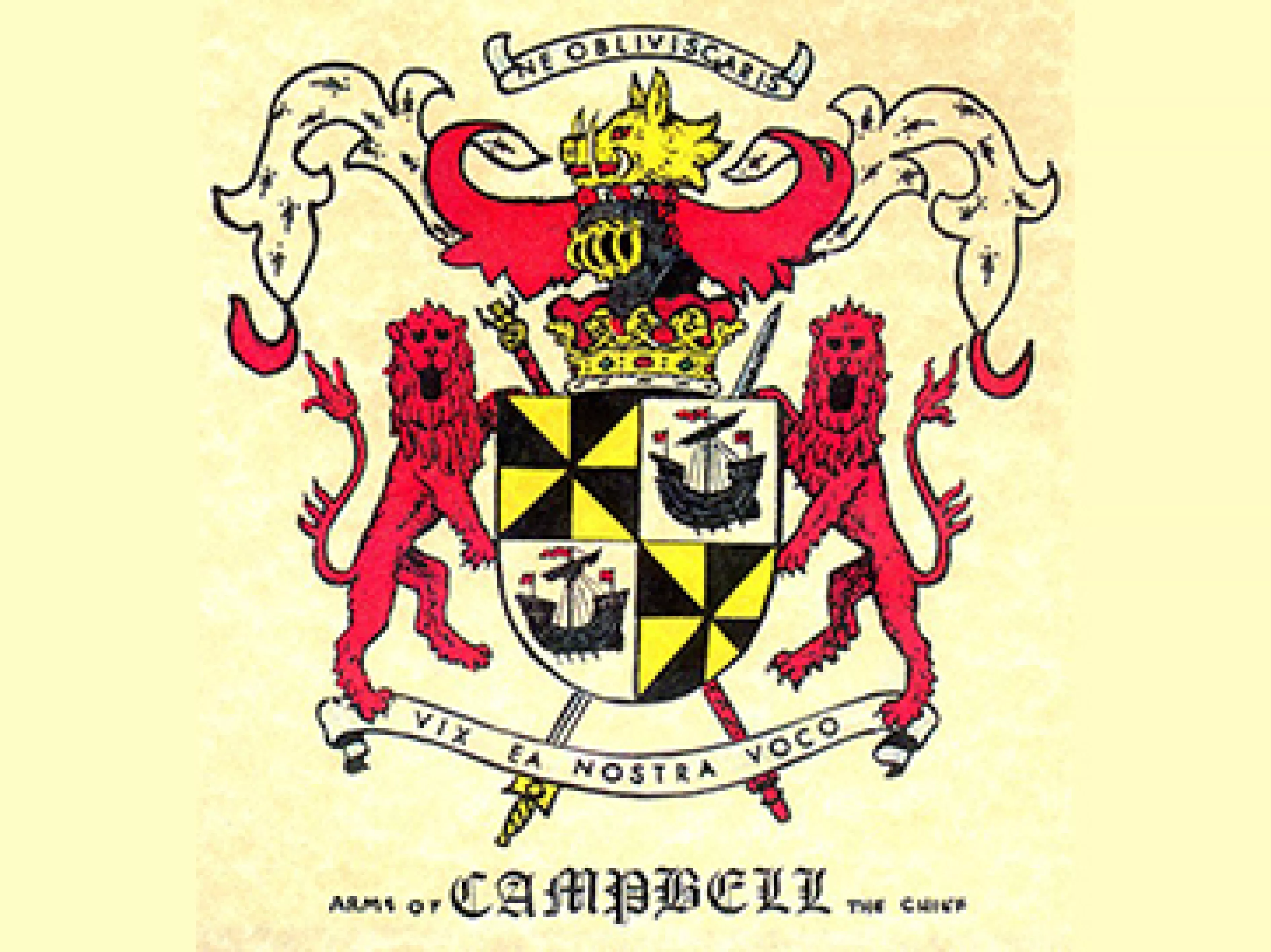

Titles and Honors: He succeeded as the Chief of the Honorable Clan Campbell, Mac Cailein Mór on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 19th Lord Campbell [S., 1445] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 18th Earl of Argyll [S., 1457] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 18th Lord Lorne [S., 1470] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 12th Lord of Kintyre [S., 1626] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 11th Baronet Campbell, of Lundy in Angus, co. Forfar [N.S., 1627] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 9th Duke of Argyll [S., 1701] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 9th Marquess of Kintyre and Lorne [S., 1701] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 9th Earl of Campbell and Cowall [S., 1701] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 9th Viscount of Lochow and Glenyla [S., 1701] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 9th Lord of Inverary, Mull, Morvern and Tiree [S., 1701] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 5th Baron Sundridge, of Coomb Bank, Kent [G.B., 1766] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 6th Baron Hamilton of Hameldon, co. Leicester [G.B., 1776] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded as the 2nd Duke of Argyll [U.K., 1892] on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded to the title of Hereditary Master of the Royal Household in Scotland on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded to the title of Hereditary Keeper of the Great Seal of Scotland on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded to the title of Hereditary Keeper of the royal castles of Dunoon, Carrick, Dunstaffnage and Tarbert on 24 April 1900.

He succeeded to the title of Admiral of the Western Coasts and Isles on 24 April 1900.

He was appointed Knight Grand Cross, Royal Victorian Order (G.C.V.O.) on 2 February 1901.

He was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Law (LL.D.) by Cambridge University, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, England, in 1902.

He was awarded the honorary degree of Doctor of Law (LL.D.) by University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland, in 1907.

He held the office of Chancellor of the Order of St. Michael and St. George.

He held the office of Private Secretary to his father at the India Office between 1868 and 1871.

He held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) (Liberal) for Argyllshire between 1868 and 1878.

He was appointed Knight, Order of the Thistle (K.T.) on 21 March 1871.

He was appointed Privy Counsellor (P.C.) on 17 March 1875.

He was appointed Knight Grand Cross, Order of St. Michael and St. George (G.C.M.G.) on 14 September 1878.

He held the office of Governor-General and Commander-in-Chief of Canada between October 1878 and 1883.

He was awarded the Order of the Black Eagle of Prussia.

He held the office of Governor and Constable of Windsor Castle in 1892-1914.

He held the office of Member of Parliament (M.P.) (Liberal Unionist) for Manchester South between 1895 and 1900.

He was awarded the Royal Victorian Chain 1902.

He was appointed Knight of the Garter 1911.

He held the office of Lord-Lieutenant of Argyllshire between 1900 and 1914.

He has an extensive biographical entry in the Dictionary of National Biography.

Preceded by: father George John Douglas Campbell, 8th Duke of Argyll (S), 1st Duke of Argyll (UK), KG, KT, PC, FRS, FRSE

Succeeded by: nephew Niall Diarmid Campbell, 10th Duke of Argyll (S), 3rd Duke of Argyll (UK)

Burial: John George Edward Henry Douglas Sutherland Campbell, 9th Duke of Argyll (S), 2nd Duke of Argyll (UK) was interred at Kilmun Parish Church and Cemetery Kilmun, Argyll and Bute, Scotland.

Citations:

The Lorne papers at NA, MG 27, I, B4, consist of microfilm copies of material borrowed in 1966 from the 11th Duke of Argyll, along with some original documents. Sir John A. Macdonald’s correspondence with him is found in NA, MG 26, A, vols.80–83.

A listing of Lorne’s publications, including a number of substantial monographs, appears in the National union catalog. His Canadian pictures, drawn with pen and pencil is worth reading, as is The Canadian north-west . . . (Ottawa, 1881). His autobiography, Passages from the past (2v., London, 1907), is disappointing for those interested in Lorne’s marriage and later life in England, but it is good on his early life and travels, including his time in Canada.

The leading secondary source on Lorne is R. M. Stamp, Royal rebels: Princess Louise & the Marquis of Lorne (Toronto and Oxford, 1988). As the title suggests, it deals with both figures, cleverly interleaving one life with the other. It is based on an extensive survey of primary sources and a wide range of secondary materials on both sides of the Atlantic. W. S. MacNutt, Days of Lorne: from the private papers of the Marquis of Lorne, 1878–1883, in the possession of the Duke of Argyll at Inveraray Castle, Scotland (Fredericton, 1955), is more discursive, using Lorne’s own words, but without the comprehensive modern research that went into Stamp’s study. p.b.w.]

Times (London), 22 March 1871, 4 May 1914. [J.] B. Burke, A genealogical and heraldic dictionary of the peerage and baronetage . . . (53rd ed., London, 1893); ed. [H. F. Burke] (60th ed., 1898). Canadian men and women of the time (Morgan; 1912). Debrett’s peerage, baronetage, knightage, and companionage . . . (London, 1907). Sandra Gwyn, The private capital: ambition and love in the age of Macdonald and Laurier (Toronto, 1984). J. B. Paul, The Scots peerage . . . (9v., Edinburgh, 1904–14), 1: 389; 8: 360, 362. Rebecca Sisler, Passionate spirits; a history of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts, 1880–1980 (Toronto, 1980).

P. B. Waite, “CAMPBELL, JOHN GEORGE EDWARD HENRY DOUGLAS SUTHERLAND, Marquess of LORNE and 9th Duke of ARGYLL,” in Dictionary of Canadian Biography, vol. 14, University of Toronto/Université Laval, 2003–, accessed October 11, 2018, http://www.biographi.ca/en/bio/campbell_john_george_edward_henry_douglas_sutherland_14E.html.